Historians offer vastly different estimates of the percentage of people who supported the American Rebellion and those remaining loyal to the British Crown. However, all historians point to a sizable group that did not advocate for either side. Approximations of the non-committed citizenry range from twenty to sixty percent.[i] A significant estimation difficulty is that many people did not hold firm and consistent Rebel or Loyalist views throughout the Rebellion, as many residents changed their loyalties depending upon the movement of Rebel or British troops into and out of their communities. Additionally, another cohort exhibited ambiguous loyalties and did enough to convince each side that they were not a threat and supported their cause.

Thriving farmer and merchant David Bush (1733-1797) was a prototypical person who demonstrated unclear loyalties during the eight-year conflict. A son of a Dutch settler, Bush (Anglicized from Bosch), owned over two hundred acres of prosperous farmland in coastal Southeast Connecticut. He operated a grist mill on the west shore of the Mianus River in Cos Cob, driven by the powerful Long Island Sound tides. As a result of flourishing exports to New York City and the Caribbean, he was one of the wealthiest people in the area. In the lead-up to the war and throughout its eight years, there are indications that Bush acted as a loyalist while at other times a Rebel.

Signs Bush was a Loyalist.

As early as 1765, there were clues that Bush held higher regard for the British government and its colonial laws than his neighbors.

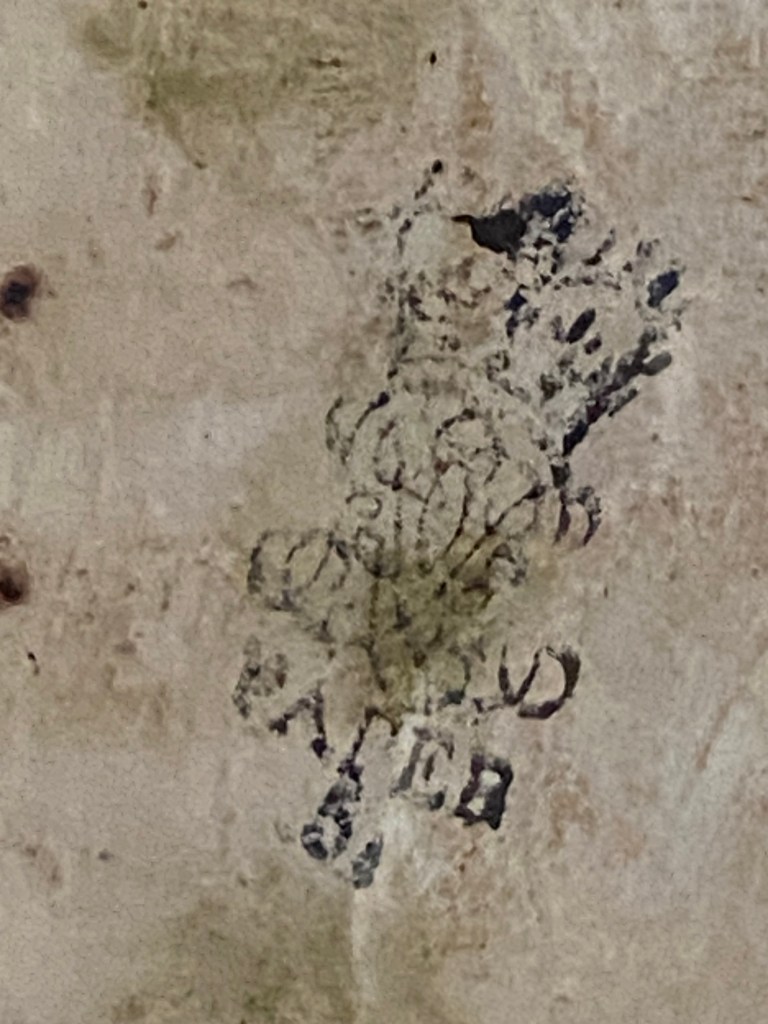

For example, there is evidence that he paid the almost universally hated stamp tax. The wallpaper in his parlor contains a stamp tax insignia on the back. Given widespread and often violent opposition, stamp tax authorities were forcibly prevented from collecting their tax in most locations. As a result, few people paid the stamp tax and even fewer Patriots. Bush was in the tiny minority of confirmed stamp tax payors.

In the early years of the armed conflict, Bush’s loyalties were not a community issue, despite providing food and other goods to the British garrison in New York City. However, when war came to southeast Connecticut in 1779 and British Maj. Gen. William Tryon raided the Cos Cob seacoast, Bush’s neighbors became concerned that he was a Loyalist. The former New York Governor ordered the burning of Rebel-owned houses along the Mianus River, including a valuable salt mill across the river from the Bush residence. However, the marauding British Army left the Bush properties untouched. To the Revolutionaries, preserving his house and grist mill signaled that Bush was a Loyalist. As a result, the Rebel government sent Bush to a Patriot prison in Fairfield, Connecticut, for refusing to sign a Patriot loyalty oath.

Another indication that Bush advocated loyalty to the British government is that none of Bush’s ten or more Black enslaved people self-emancipated to the British military. Many enslaved people escaped to British lines seeking freedom. Typically, the British welcomed runaway enslaved men and women from Rebel farms and businesses but did not accept those Loyalists owned. The fact that none of his enslaved workers sought refuge with the British Army strongly indicates Bush’s wartime loyalties.

Signs Bush was a Patriot

While there is solid evidence that Bush possessed British allegiances, there are other indications that he exhibited Rebel fidelities. For example, after several months in the Fairfield jail, the Patriot government officials released him. Bush most likely paid a hefty fine for his freedom, which aided his release into the community. Allowing him to stay in his home was a significant signal that Bush convinced the Patriot authorities of his anti-British allegiances. Other similarly-situated Loyalists fled to British lines in New York City to escape persecution and incarceration. Additionally, the community permitted Bush and his family to remain in Cos Cob after the Treaty of Paris ended the conflict. Most committed Loyalists fled with the evacuating British Army in 1783.

Summary

While Bush’s loyalties were ambiguous, his wartime behaviors did not sit well with neighbors creating long-term enmity. As compelling evidence, no one in town would marry one of his fifteen children, who, therefore, had to seek mates outside the area.[ii] Bush retained his wealth due to his ambiguous loyalties but could not regain his community standing.

Over-simplifying the past, we tend to categorize Revolutionary Era individuals as Patriots or Loyalists, but often people played both sides or switched during the war. Being overly judgmental from two hundred and fifty years later is improper, as it was a physically and economically challenging period, and many people executed questionable actions to survive. Ultimately, Bush did what he thought was right, navigating allegiances on the Rebel-British borderlands to preserve his family and fortune.

To experience ambiguous Revolutionary War loyalties firsthand, I recommend visiting the Bush-Holley house devotedly maintained by the Greenwich Historical Society.[iii] The New York Times also published a guide to visiting the site.[iv] A tour highlight is the recreated enslaved persons’ quarters above the kitchen.

[i] For a description of the controversy over the percentages of Rebels and Loyalists, see Michael Schellhammer’s Journals of the American Revolution article. https://allthingsliberty.com/2013/02/john-adamss-rule-of-thirds/

[ii] Assertion that the Bush children married outside the area is per Greenwich History Society tour guide

[iii] For a description of the Bush-Holley House and grounds, see the Greenwich Historical Society website. https://greenwichhistory.org

[iv] For a link to the New York Times tour guide, see https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/07/nyregion/bush-holley-house-cos-cob-connecticut.html

Discover more from Researching the American Revolution

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You are amazing Gene! This is really well done. I think it is unfair that the perceived crimes of the father were held against his children. Katy

>

LikeLike

Good analysis Gene. I would guess the “uncommitted” or flexible would be on the higher end. I think you told me your boy Ethan Allen showed quite a bit of flexibility when it came to business matters. Also, I read that the British held back their Army and and weren’t as harsh as they could have been putting down the rebellion because they believed, in the end most people were loyalist at heart. Doug

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. I agree the British over estimated the number of Loyalists.

LikeLike