Book Review

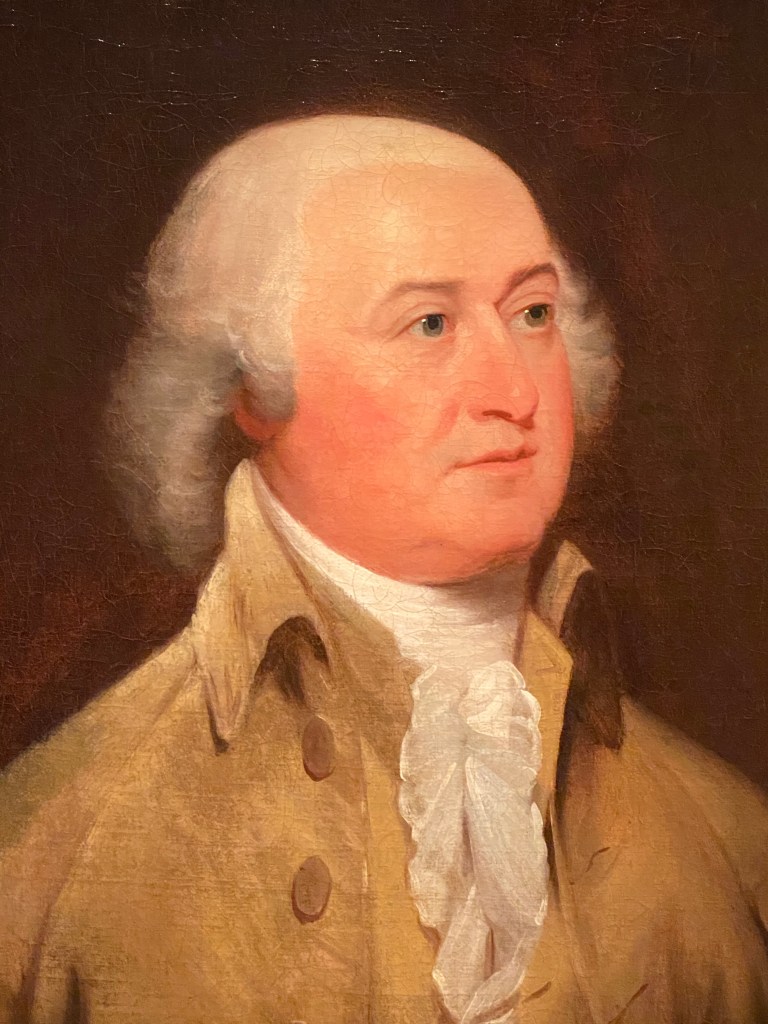

Holdzkom, Marianne. Remembering John Adams: The Second President in History, Memory and Popular Culture. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2023.

Displaying a life-long interest in John Adams, historian Marianne Holdzkom delves into the founder’s character as portrayed by contemporaries, scholars, and popular writers. Through extensive study, she addresses the question, “Who was John Adams’ as interpreted by historians. Just as interesting, the history professor addresses ‘Who is John Adams’ in our popular memory today. She analyzes the history of works depicting Adams by poets, playwrights, filmmakers, and public historians, influencing today’s public persona. In addressing these two questions, she illustrates the tension and differences between how colleagues and enemies viewed John Adams and how the public remembers him today. Additionally, the Colonial/Revolutionary Era specialist argues that the public’s views of John Adams, as shaped by cultural media over the last fifty years, are not the professional biographers’ views, leading to significant distortions and inaccuracies.

Eye-catching openings, clear organization, and easy-to-follow transitions are three of the monograph’s strengths. Professor Holdzkom organizes her work with an introduction, nine chapters, and a conclusion. The first three chapters introduce John Adams and present an interesting overview of the scholarly historiography. The second president’s descendants wrote the first authoritative though biased biography. As the family opened John’s and Abigail’s papers to researchers, independent, disinterested biographies emerged. While scholarly biographers such as Page Smith penned excellent works for the academic community, Adam’s most prominent biography appeared at the start of the twenty-first century when popular historian David McCullough’s book became an instant hit, appearing on the New York Times best-seller list and earning a Pulitzer Prize. However, its reception among academic historians was mixed, as many believed McCullough engaged in inappropriate hagiography, overlooking critical flaws. For example, historians condemn the second president for signing the infamous Alien & Sedition Acts (147). The controversy became so notable that a new label, “founders’ chic,” emerged, an appellation describing overly favorable views of Revolutionary Era leaders. Holdzkom notes unspecified gaps in McCullough’s work; readers may want to understand her opinions on the famous historian’s work better.

In the following four chapters, Professor Holdzkom analyzes John Adams as depicted in art and culture. Leveraging her drama background, she describes the influence of popular media in changing the public’s memories. The most significant single impact was the 1970 play 1776. She discerningly notes that in this Broadway production, the character of John Adams was a mashup of the historical John Adams and his cousin Sam. While 1776 ignited widespread interest in Adams, it unfortunately inappropriately tagged him as “obnoxious and disliked.” Holdzkom thoroughly debunks this one-dimensional notion, revealing Adams’s more complex character than this theatrical refrain. In her words, the patriot leader was “crusty, but warm, intelligent but volatile, awkward but effective, blunt but easily wounded by words and actions of others. He loved – and hated – deeply” (14). Further, he was no marble statue (34).

The last two chapters describe how citizens of Quincy, Massachusetts commemorate its most famous denizen. Here, the impact of McCullough’s book is also felt. After its publication, town residents erected statues and parks to recognize Adams and capitalize on his newly prominent place in popular memory. Completing her story, Professor Holdzkom interviews public historians employed at the Adams National Historical Park in Quincy. The park interpreters offer valuable insights over and above published biographies and cultural depictions. The park rangers assess Adams as exhibiting a “special imagination and empathy,” a “warm man, capable of deep loyalty and friendship,” and a “marshmallow” who doted on his grandchildren (190). This is an excellent illustration that not all insights emanate from the archives, and visiting public history sites is necessary for historians to write fulsome histories.

Finally, Professor Holdzkom notes that there is no John Adams memorial on the Washington, DC mall, despite his prominent role in the American Rebellion. President Donald Trump and President Joe Biden appointed two members each to a commission to commemorate John and Abigail Adams, John Quincy Adams, and other members of the Adams family. However, the path forward is still being determined as congressional leaders have yet to appoint eight members. Despite the lack of a monument, the Revolutionary leader left sage advice to his successors in DC. A quote from the White House’s first resident is prominently displayed on the state dining room mantle. “I pray Heaven to bestow the blessings on this House and all that shall hereafter inhabit it. May none but honest and wise Men ever rule under this roof.” Just before his death, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered Adams’ wish inscribed over the fireplace, demonstrating his respect for the founder (28). With a modification to include women, maybe a visible reminder at the seat of power is the best way to remember the sagacious founder.

Remembering John Adams is a worthy addition to your library. It is especially valuable for those interested in “humanizing” a founder and learning how Adams’s present-day reputation evolved. Additionally, the book is instructive for those seeking to write histories of memory, which is vitally important as we begin to celebrate America’s 250th birthday in 2026. Given the impressive depth of Holdzkom’s John Adams knowledge, she might have told us more of her opinions, such as her views on the gaps in David McCullough’s book. Perhaps such a sequel is in the offing.

After reading Professor Holdzkom’s engaging book, I don’t believe the oft-repeated 1776 refrain that John Adams was “obnoxious and disliked.” On the contrary, I would have relished sitting down with the Revolutionary over a beer and talking politics. Adams would have cogently outlined his policy positions lively, civilly, and based on facts. As importantly, the founder would carefully and respectfully listen to my views. He would make decisions with integrity by assessing the pros and cons of input from me and others. Who could ask for more of our nation’s leaders?

Discover more from Researching the American Revolution

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.