Book Review

Grubb, Farley Ward. The Continental Dollar: How the American Revolution Was Financed with Paper Money. Markets and Governments in Economic History. Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2023.

“Contempt for Congressional money gave rise to the first national slogan – “not worth a Continental.”[i]

The widely embraced aphorism “not worth a Continental” refers to the calamitous outcome of the Continental Congress’s monetary and fiscal policies during the American Revolution. The standard story goes as follows. Lacking taxation powers, Congress resorted to the ill-advised printing of money with no gold or silver backing. Economists refer to this currency type as fiat money, which, if abused, can lead to disastrous consequences. As the war dragged on, Congress merely turned the printing press to manufacture more and more money. The increasing unbacked dollars led to a precipitous value decline and runaway inflation. As a result, five years into the war, the Continental dollar became worthless. A wagonload of currency narrowly purchased a wagonload of supplies for the Continental Army.[ii] The Continental Dollars were so worthless that “a barber in Philadelphia papered his shop with bills, and a dog was led up and down the streets, smeared in tar, with this unhappy money sticking all over him…[iii] Failed congressional financial management inspired the derisive refrain, “not worth a Continental.”

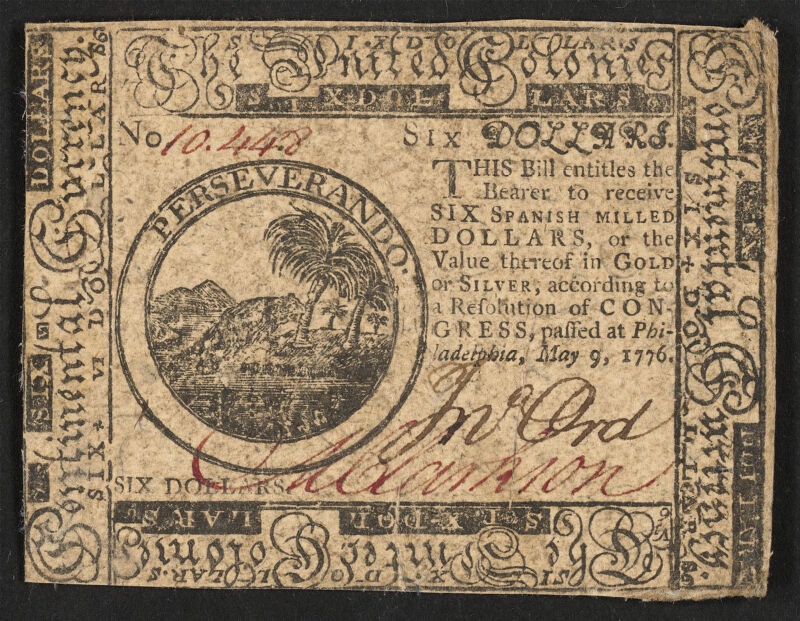

While widely embraced, Farley Grubb thoroughly debunks this interpretation in his new book on how Congress financed the Revolutionary War. First, the Continental dollar was a zero-coupon bearer bond, not a fiat currency. Congress promised the bond owner the face amount of the bond at a future date. As expected by Congressional members and citizens, the bond’s future redemption value is traded at its present value. The difference between present and future values was expected time discounting, not value depreciation. Understanding the time value of money, knowledgeable bondholders discerned the difference between time discounting and currency depreciation. Eighteenth-century Americans had experience with this type of government finance as various colonies used the same zero-coupon bearer bond approach to finance military expenditures during the French and Indian War. These colonial bonds held their actual time-discounted value, with some redeemed in full as late as the 1790’s.

Through meticulous research and quantitative analysis, Professor Grubb establishes that Congress issued two hundred million Continental dollars, a figure lower than previously thought. They issued the dollars in large, bizarre denominations to reduce the number of bills required to pay the soldiers and to inhibit their use in transacting daily business. He divides the history of Continental dollar emissions into three periods. From their first issuance in late 1775 to late 1776, the Continental dollars traded at a premium to their time-discounted values. He surmises that the initial appreciated values resulted from the initial patriotic fever and the new ability to transact across state lines. The bond’s appreciation waned for the next two years, with the bonds selling at their time-discounted values. However, starting in 1779, the Continental dollar suffered runaway depreciation, with its current transaction values approaching zero. As a result, the shunned Continental dollar ceased to be used as a medium of exchange by 1780.

Grubb disputes that merely printing Continental dollars led to his ruinous outcome. Alternatively, he posits that Congressional inattention to redemption dates in several dollar emissions confused the public on how to time value the bonds. Further, Congress encouraged states to make the Continental dollars legal tender, leading to increased use and defeating their zero-coupon features. Finally, the implied tax rates to generate redemption funds became exorbitant within the stated bond trade-in periods. The economics professor asserts that ill-advised Congressional actions led to value destruction and not using zero-coupon bonds to finance the war. As evidence, the points to their successful colonial use during the French and Indian War.

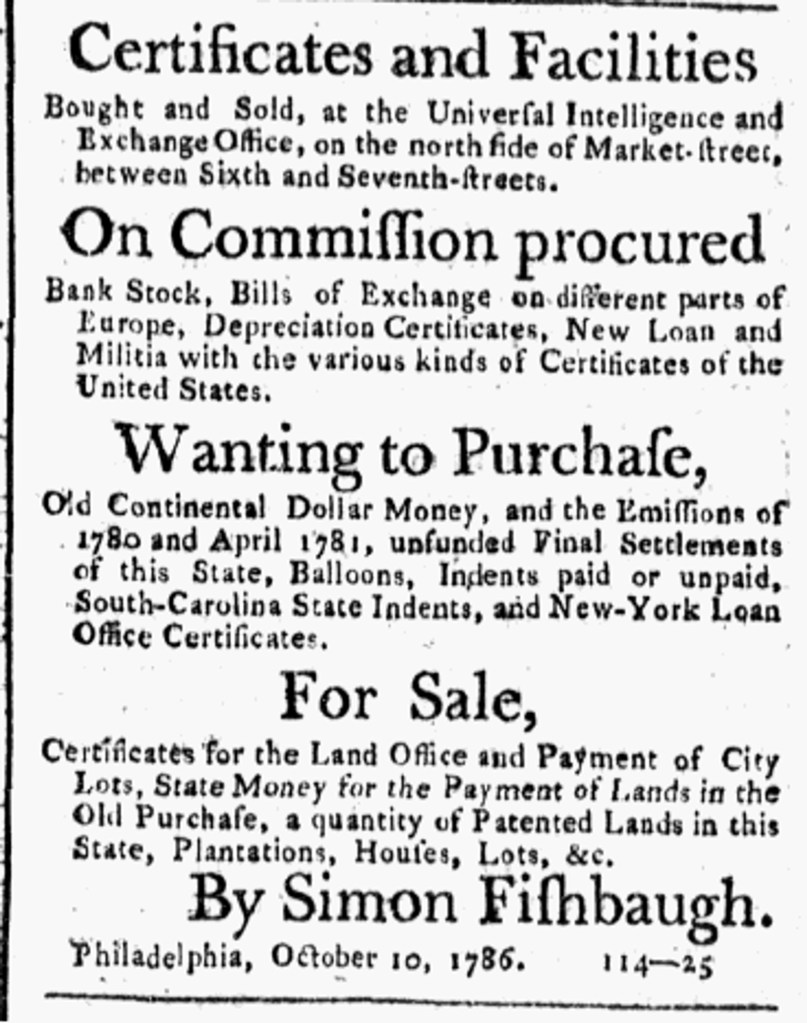

While the Continental dollar ceased to be a medium of exchange after 1780, the story does not end there. Congress requested that states purchase outstanding Continental dollars either by specie or in lieu of tax payments and established a remittance schedule. The redeemed bonds were to be sent to the US treasury for burning. While Congress’s credibility was at stake, complete State remittances were uneven, with only three states, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Delaware filling their 1779 and 1780 quotas. Virginia and New York partially complied. The remaining eight states ignored the remittance requirements. By 1790, approximately sixty percent of the two hundred million Continental dollars were redeemed.

The new Congress enacted the Funding Act of 1790 to repudiate the outstanding Continental dollars. Professor Grubb argues that the new Federal government could afford to repay the outstanding bonds but chose not to do so. The resulting default provided the nascent government with a positive net worth with revenue-generating abilities significantly more than its operating expenses. This strong financial position made the United States attractive to foreign and domestic lenders and set the new nation on a more solid financial footing.

Finally, Grubb avers (and this reviewer concurs) that Revolutionary Era citizens did not use the phrase “not worth a Continental.” His research did not locate any contemporary use of the iconic phrase in period diaries, letters, newspapers, or other documents. The earliest known use of the adage is in the mid-nineteenth century. Historians likely invented the apocryphal phrase to compare the Revolutionary Era Continental dollars to the 1800s political disputes over gold, silver, and other monetary politics.[iv] Unfortunately, the fictional phrase continues to be repeated, which provides a further example of the need to be a skeptical reader.[v]

The economic historian’s arguments are based upon an impressively extensive data compendium, including twenty-seven data tables and five statistical appendices. The author compiled this information over twenty years of research, producing twenty-seven articles and monographs. Readers interested in statistics will enjoy the equations and other statistical analyses that support the writer’s conclusions. While the author’s arguments are data-driven, additional perspectives of Continental dollar users might be helpful. For example, Grubb assumes that transactors understand the nuances of time-discounting and share a common view of a six percent discount rate. A more realistic understanding of variances would help readers understand the uncertainty of accepting Continental dollars in transactions. Additionally, he might have addressed the impact of widespread counterfeiting on the dollar’s value.

Despite these minor quibbles, I recommend The Continental Dollar as the “go-to” resource for understanding Congressional war-time funding and monetary policies. It is time to bury that old saw, “not worth a Continental.” Hopefully, by embracing Grubb’s analyses, today’s historians will not perpetuate this made-up notion.

For another review of The Continental Dollar, see Gabriel Neville’s review in the Journal of the American Revolution.

[i] Don Higginbotham, The War of American Independence Military Attitudes, Policies and Practice, 1763-1789 (Norwalk, Connecticut: The Easton Press, 1971), 290.

[ii] George Washington quoted in, John E. Ferling, Winning Independence: The Decisive Years of the Revolutionary War, 1778-1781 (New York London, Oxford, New Delhi Sydney: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021), 235.

[iii] John Fiske, The American Revolution (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1891), II:198-9.

[iv] Higginbotham, The War of American Independence Military Attitudes, Policies and Practice, 1763-1789, 288.

[v] For example, Harvard University Library website https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/american-currency/feature/continental-currency. Other examples abound.

Discover more from Researching the American Revolution

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.