Book Review

Crawford, Alan Pell. This Fierce People: The Untold Story of America’s Revolutionary War in the South. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2024.

“This Fierce People,” a quote from Edmund Burke’s speech to Parliament a month before the outbreak of hostilities on Lexington Green, titles a grand, easy-to-read narrative of the American Revolution in the Southern colonies. A Whig (opposition) member of the House of Commons and a critic of the British government’s American policies, Burke failed to convince his colleagues to enact conciliatory measures to keep the peace with the thirteen American colonies. Just as British political leaders misunderstood America’s resolve, the Richmond, Virginia resident author asserts that Revolutionary War historians have over-emphasized the early conflict in the northern colonies, leaving the impression that the conflict was “George Washington’s War” (4). As evidence, he cites that a more significant percentage of the eight-year war occurred in the southern colonies, while Washington’s army remained relatively inactive in the north. With his first book in five years, the author seeks to rectify this imbalance with a one-volume account of the Revolutionary War in the Southern four colonies.

A volunteering officer born in Bavaria, Johann von Robais, Baron de Kalb, anchors the early part of the narrative. De Kalb sailed with Marquis de Lafayette to America to fight for the Rebels. Congress named him a major general, and Washington sent de Kalb into the Southern colonies to serve under Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates. Crawford appropriately gives the capable and brave de Kalb his due. The former French officer courageously led his division at the disastrous battle of Camden, South Carolina, sacrificing his life in the heroic but hopeless stand to stem the British advances. Many other Patriots lived because of de Kalb’s resolute actions. Featuring de Kalb and the destruction of the Rebel army at Camden set the stage for difficult campaigning ahead for the Rebels and the rest of the former U. S. Senate speechwriter’s account.

Depicting over one hundred battles in a one-volume monograph, the author avoids copious combat details, providing simple but cogent battle descriptions. Interspersed between battles are portrayals of what it was like to live as a civilian in such active combat. More so than in the North, the Southern theater was a bitter civil war in which atrocities and wanton destruction regularly occurred. Crawford chronicles several specific civilians and how they survived the chaos. For example, he debunks the notion that planters’ wives were “fragile and delicate ladies,” citing the experiences of Eliza Pinckney, who ably ran three plantations after the death of her husband (75). As with Eliza, the author provides fascinating background information when introducing new people, nodding to readers unfamiliar with the Revolutionary Era.

Storytelling is the veteran journalist and political analyst’s strong suit. The book is laced with vignettes that engender reader interest and comprehension. For example, the story of Christian Huck, a Loyalist militia leader, illustrates the wide-ranging destruction and vicious violence among the warring Carolina residents. As with many cycles of death and destruction, Huck, later in the conflict, loses his life in a sneakily executed attack, partially motivated by retribution.

Historical storytelling can also stray from substantiated events and become a strength overdone. All stories, especially the “good ones,” need to be viewed with “a pinch of salt.” Historical best practices include avoiding nicknames recited from secondary sources, evaluating primary sources for bias, corroborating primary sources, and assessing stories for relevancy, regardless of their interest. Several instances of these canards should be skeptically approached.

Repeating nicknames cited in biographies and other secondary sources, especially those written in the nineteenth century, can misrepresent how contemporaries viewed their military leaders. For example, Crawford refers to Continental Army Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates as “Granny Gates” and British Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton as “Bloody Ban.” Revolutionary-era observers did not use either of these post-war appellations. These mischaracterizations leave readers with unfounded impressions.[i]

Understanding personal biases is also critical, as many contentious factions existed among the Patriot officers. For example, the author cites Nathanael Greene’s and Alexander Hamilton’s criticism of Horatio Gates after his disastrous defeat at Camden (68). Greene and Hamilton supported Washington’s struggle with Gates for Continental Army leadership. They were most happy to denigrate Gates’ performance at Camden, ending a threat to Washington’s leadership. Later, after Congress named Greene as the Southern Army commander, he assessed that Gates had been dealt a bad hand at Camden, a critical fact omitted in This Fierce People.[ii]

Lacking appropriate primary source corroboration, the author and numerous other historians repeat a supposed incident during the Battle of Guilford Court House. He cites Maj. “Light Horse Harry” Lee’s Memoirs, in which the British General Charles Lord Cornwallis orders, to the horrors of his second in command, two three-pounders to fire grapeshot into a mixed melee of British and American soldiers to break up the Rebel assault (218). However, Lee was absent during this alleged incident, and no British or American battlefield source corroborated Lee’s story. An expert on the battle concluded, “It is unlikely the incident as it has come to be described ever happened and that it was either a rumor that Lee had heard or something he developed in the interest of a good story.”[iii]

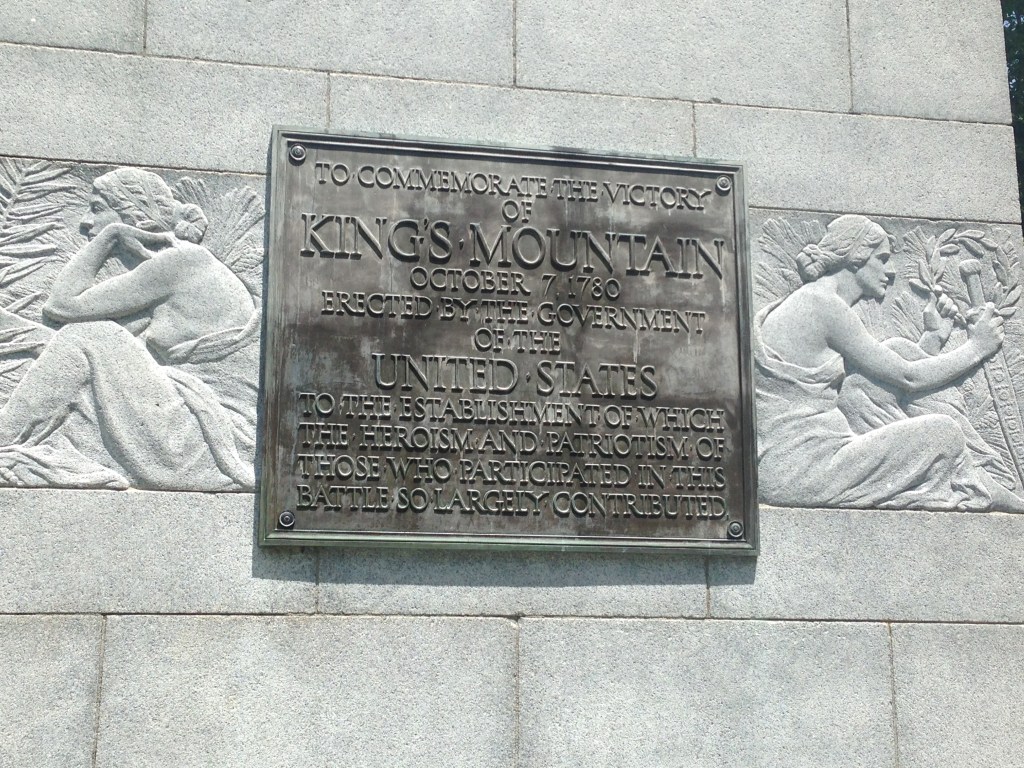

Lastly, only stories vital to the author’s thesis are valuable to the readers. The author includes the tale of Virginia Sal and Virginia Paul, two purported mistresses of the British commander, who were present at the Battle of Kings Mountain. In 1882, the original source, Lyman Draper, interviewed area residents and introduced his story with “Tradition has it….” citing oral interviews.[iv] Draper reports that Virginia Sal died in the battle and was thought by some to be buried with the British commander, Maj. Patrick Ferguson, while Crawford avers that both women were killed and buried with the British Major (129). Regardless of these women’s fates, the story of Ferguson’s mistresses is irrelevant, added for no good reason, and does not contribute to the author’s thesis that the American Revolution was more important in the South after 1778.

On the other hand, apocryphal stories often aid understanding if they are correctly identified as such and contribute to the argument. For example, Crawford assesses the supposed notion that Col. Francis Marion distributed Loyalist and British plunder to families of needy Patriots as not a fact but a legend (224). However, the apocryphal story illustrates that Marion enjoyed excellent relationships with the South Carolina community. Another example is the story that Patrick Ferguson had a chance to shoot George Washington before the 1777 Battle of Brandywine but decided that it was not gentlemanly to kill an officer from behind the cover of a dense forest. While Ferguson went to his grave believing that he passed up an opportunity to kill the Rebel commander-in-chief, the author asserts that “Historians have been reluctant to credit this too-good-to-be true story, and their reluctance is understandable” (96). The story is relevant to whether Ferguson acted as a gentleman in the Southern theater, which the perceptive author concludes was debatable.

This Fierce People is most appropriate for individuals who have read an introductory book on George Washington and the outbreak of the Northern Rebellion but want to learn more about the Southern struggle. The general appeal monograph is not likely to interest scholars seeking new insights and previously unexamined primary sources. However, the author does an excellent job of describing the civil war nature of the Southern conflict and its lawlessness. The Carolinas, especially, experienced extensive marauding and stealing by both sides, resulting in horrific brutalities, which Crawford makes sure are not overlooked as in many other accounts. One can quibble with the level of historical skepticism, but writing a cogent overview of such a fabled conflict is complicated due to past historians’ retelling of uncorroborated stories. As the author sets out to accomplish, his work will better recognize the importance of the Southern War.

[i] John Knight, War at Saber Point: Banastre Tarleton and the British Legion (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2020), 28.

[ii] To George Washington, December 7, 1780, Nathanael Greene et al., The Papers of General Nathanael Greene (Chapel Hill: Published for the Rhode Island Historical Society [by] the University of North Carolina Press, 1976), 544–45.

[iii] Lawrence Edward Babits and Joshua B. Howard, Long, Obstinate, and Bloody: The Battle of Guilford Courthouse (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 161–62.

[iv] Draper, Lyman Copeland., Allaire, Anthony., Shelby, Isaac. King’s Mountain and Its Heroes: History of the Battle of King’s Mountain, October 7th, 1780, and the Events which Led to it. United States: P.G. Thomson, 1881, 292.

Discover more from Researching the American Revolution

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.