Movie Review

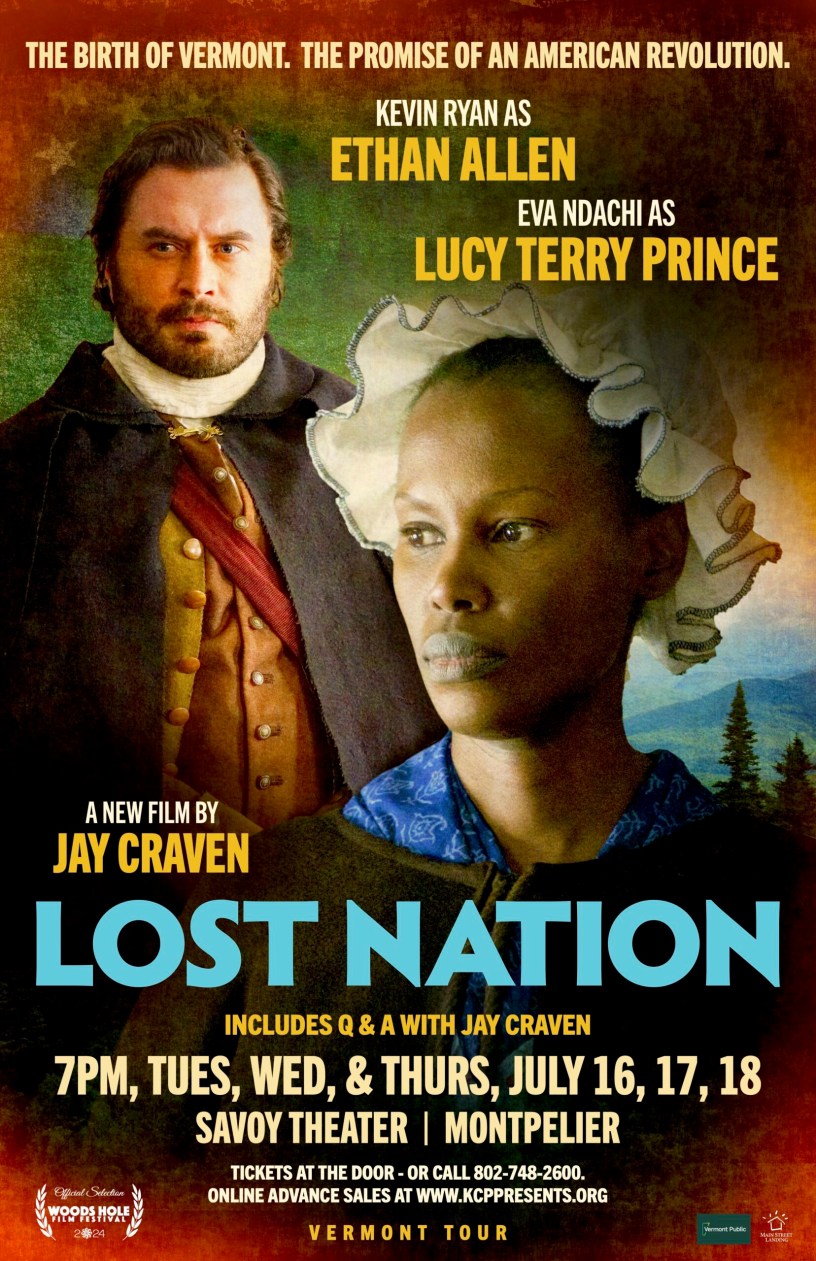

Lost Nation, Directed by Jay Craven, written by Jesse Bowman Bruchac, Jay Craven, and Elena Greenlee, Kingdom Country Productions, Release date June 1, 2024.

Filmed in Nantucket and Vermont, Lost Nation chronicles the bitter Revolutionary Era conflict over land ownership and governance of the modern-day state of Vermont. In the years leading up to the American Revolution, New Hampshire and New York Royal governors issued conflicting land grants. The dispute burgeoned into a violent but not deadly clash between the Green Mountain Boys, led by the notorious Ethan Allen, who extra-legally asserted their New Hampshire-issued land grants against the Yorkers enforcing their New York-based land ownership. In his tenth feature film, Jay Craven weaves the story of Ethan Allen, a famous Vermont founder, with the previously obscure story of Lucy Terry Prince, a formerly enslaved woman protecting her family from re-bondage and prejudice.

Lucy Terry Prince authored the poem Bars Fight, the first known work of African American literature. The thirty-line ballad recounts the August 21, 1746, Native American raid on Deerfield, Massachusetts. Prince chronicles the death of eight residents and the capture of another in a bars, an eighteenth-century word for meadow. Residents and friends passed the poem orally to succeeding generations until Josiah Gilbert Holland published the ballad in his 1855 History of Western Massachusetts. Prince and her husband, Abijah, purchased their freedom from a Massachusetts enslaver. An aspiring farmer, Abijah received a portion of his French and Indian War militia commander’s property in exchange for assisting in deforesting the land and making necessary improvements for grain cultivation. As a result, the family moved to the small town of Guilford, Vermont, to cultivate their new property.

Unfortunately, the new homestead did not lead to the peaceful life of free people, as the family’s land was in the crosshairs of the New Hampshire Grant/Yorker conflict. Shortly after arriving, a neighbor, John Noyes, developed designs on the Princes’ property. He destroyed crops, fences, and other property to force them out. He threatened the freedom of the Princes’ children as Lucy and Abijah brought their children to Vermont without legal manumission papers. Noyes also employed menacing threats and intimidation to encourage the Princes to leave Guilford and sell their property cheaply to him. With courage and fortitude, Lucy and Abijah fought back. They took Noyes to court, winning judgments but never receiving proper restitution.

Noyes, a supporter of New York, was also an antagonist for Ethan Allen and the New Hampshire grantees. In the movie, Allen travels to Guilford to confront Noyes but does not provide the Prince family with any protection. As the American Rebellion continued, Allen and the Green Mountain Boys gained the upper hand against the Yorkers. In 1777, Vermonters declared their independence and adopted a constitution partially outlawing slavery. While Vermont sought to join the thirteen colonies, the Continental Congress demurred due to pressure from New York delegates. As a result, Ethan and Ira, his youngest brother, toyed with the potential to rejoin the British Empire to secure their land titles and protect settlers from Yorker confiscation. While their traitorous efforts are ambiguous, the film portrays Ira Allen as the brother most interested in rejoining the British Empire. At the same time, Ethan appears to demur, using the British negotiations as a stalling tactic. Whatever their intentions, the British dalliance ended with the Rebel victory and the 1791 admission of Vermont into the United States.

In addition to sharing the same antagonist, Craven highlights additional similarities between the Green Mountain Boy leader and the poet. They both were authors, with Allen penning two published books and numerous political and philosophical pamphlets. While Lucy has no other surviving poems, she was highly regarded as an intelligent thinker and likely produced more poetry that has been lost to history. Both were well-spoken and persuasive, had the courage of their convictions, and were unafraid to speak their minds. They strongly advocated for their families and themselves. Both fought against Yorkers for their property, but for different reasons, achieving different results. Allen preserved the New Hampshire grantees’ titles while the Princes lost their farm to debts. As a result, Allen achieved notoriety as a Vermont founder, and Prince’s fight for equality disappeared into relative obscurity. Craven suggests that people should honor both legacies today.

Viewers should heed the filmmaker’s caution in the opening section and not obsess over historical errors, as the film is historical fiction. However, an essential aspect of the film leaves a misleading impression. Audiences are tantalized by the impression that Ethan Allen likely murdered a Yorker rival, Crean Brush, while a British captive in New York City. This assertion reflects the speculative musings of two Vermont historians without a supporting primary source.[i] For this to be true, Allen would have to escape from jail, travel several miles, commit the murder, and sneak back into jail, all without being spotted. Contemporary sources cite Brush’s death as a suicide by either a pistol shot to the head or a slit to the throat. In any case, Brush was a troubled man with a history of alcoholism and declining prospects. An additional fact not pointing to Allen as the killer is his prior and future actions as a vigilante Green Mountain Boy, which included intimidation and property destruction but not murder. The intimation that Allen slays Brush leaves the wrong impression about Allen. Readers interested in a more detailed description of Crean Brush’s last days should consult an article in the Journal of the American Revolution.

While not accurate in all the details, the film provides valuable history lessons. Just because the 1777 Vermont Constitution outlawed slavery does not mean that all enslaved people received freedom. Unscrupulous residents could forcibly transfer free black citizens to slave-holding states or deprive them of their citizenship rights. Further, despite the legal end of slavery, racial discrimination continued, and life for Black Vermonters could be harsh and dangerous.[ii] While Vermont was an early state to end legal slavery, racial biases inhibited Lucy and her family from full access to citizenship rights.

In addition to a poignant window into the lives of early Vermont settlers, the movie demonstrates that many current Vermont residents’ genealogies date back to the Revolutionary Era. Two of the story’s prominent characters, Governor Thomas Chittenden and Yorker leader John Noyes served in the early Vermont governments. Today, two of their descendants serve in the current Vermont legislature: Thomas Chittenden in the State Senate and Daniel Noyes in the Assembly. While their forefathers were on opposite sides, the current legislators represent the same political party. In the film, Samuel Adams plays his Boston radical ancestor in another noteworthy family connection. It would have been interesting if the filmmakers had identified and included the living descendants of Lucy and Abijah.

Viewers will recognize that Lost Nation was a “labor of love” by the filmmaker, who first encountered Ethan Allen’s story as a young adult. The duo-lead character story required more than three dozen filming locations in Vermont and Massachusetts and forty-three speaking parts. Craven augmented his thirty-person professional film crew with forty-five students from fourteen New England colleges in a remarkable twist. Innovatively, crowdfunding provided a portion of the $2.1 million production cost. The initial movie rollout includes showings in one hundred and fifty Vermont and New England towns.

I heartily recommend the film to all as a captivating, entertaining story. The lives of Ethan Allen and Lucy Prince demonstrate that the Revolutionary Era was both progressive and messy, with inconsistent outcomes that needed to be addressed by succeeding and future generations. Hopefully, the film will move from the initial New England theater tour to a prominent streaming service this fall. Viewers in other regions will enjoy Ethan and Lucy’s contrasting stories.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

For another highly recommended Revolutionary Era story

William Hunter, the son of a British soldier in the Revolutionary War, witnessed the terrors of combat and captured and penned the only surviving Revolutionary account written by a child of a British soldier. Remarkably, Hunter immigrated to America and became a gutsy Kentucky newspaper editor and a prominent politician, businessman, and community leader.

Purchase on Amazon

[i] John J. Duffy, H. Nicholas Muller, and Gary G. Shattuck, Inventing Ethan Allen (Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 2014), 142–48.

[ii] Harvey Amani Whitfield, ed., The Problem of Slavery in Early Vermont, 1777-1810 (Barre, Vermont: Vermont Historical Society, 2014).

Discover more from Researching the American Revolution

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.