Book Review

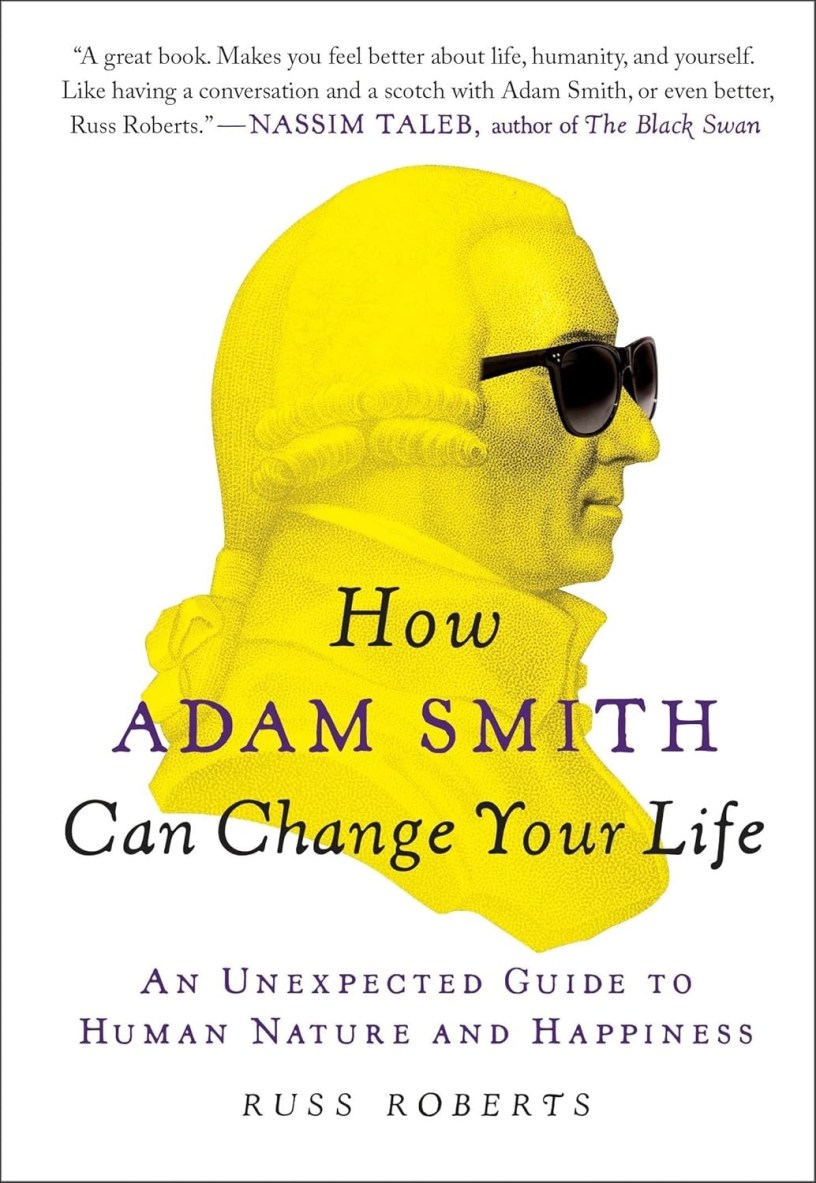

Roberts, Russell D. How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life: An Unexpected Guide to Human Nature and Happiness. New York, NY: Portfolio / Penguin, 2014.

The Enlightenment-era economist Adam Smith is renowned for his 1776 book, The Wealth of Nations. Russ Roberts, a contemporary economist and the host of the EconTalk podcast, argues that Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments (first published in 1759 and updated in 1790) is also a groundbreaking scholarly work. Roberts insightfully compares the two books: The Theory of Moral Sentiments emphasizes family, neighbors, and friends—the people around us—while The Wealth of Nations deals with impersonal exchange. Roberts succinctly states Smith’s advice: “Love locally, trade globally.”

In his book How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life, Roberts provides an accessible, compelling summary of Smith’s first book, filled with keen insights that serve as self-help recommendations. Roberts, the President of Shalem College in Jerusalem, believes that a twelve-word quote summarizes Smith’s thesis in The Theory of Moral Sentiments.

“Man naturally desires not only to be loved but to be lovely.”

Roberts unpacks Smith’s seemingly simple statement to reveal keen insights into human nature and how people act and perceive themselves.

Smith believes humans desire to be seen as honest, with integrity and sound principles. They do not want to be hated. However, people act in their interests, sometimes in concert with others. Smith’s famous example is food preparation.

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to the own interest. “

However, acting in perceived self-interest does not always result in being loved. Roberts summarizes Smith’s observation that we pursue our interests, sometimes to our detriment, following the “iron law of me.” Smith offers two suggestions to overcome this tendency. First, we should think about our actions from the perspective of an impartial spectator. Conscience is a powerful force. Smith (and Roberts) believe we are more worried about being judged by fellow humans than by god. Second, we often ignore contrary evidence to focus on things that support our world view. Today, we call this confirmation bias. Roberts notes that Frederick Hayek refers to confirmation bias as the pretense of knowledge.

Regarding the concept of loveliness, Smith presents the metaphor of the “invisible hand.” Contrary to popular belief, Smith does not illustrate the workings of competitive markets; instead, he emphasizes that acting in one’s self-interest can also benefit others. Smith’s formula for being lovely is to act with propriety, foster trust to encourage sharing emotions, and respect those around us.

Again, Smith asserts that humans can be self-delusional as we want to think of ourselves as lovely. To be lovely, we cannot use the same tools as to love. Smith believes that humans do not extend love and concern beyond our immediate circle to the same extent as our immediate family and friends. For example, Roberts notes that far away disasters do not elicit the same responses as adversities within our immediate circles. Furthermore, extending the norms of family to society can be dangerous. Hayek believes that doing so puts society on the road to tyranny.

To be lovely, we must avoid yearning for a politically powerful figure in whom we can place blind trust. Smith and Hayek warn us about the dangers inherent in whom we can trust, not just tyrants but also democratic leaders. Smith warns that society often pays more attention to the wealthy and famous than the wise and virtuous. The Scottish philosopher believes that the allure of wealth and power is a dangerous desire, a “poison to be avoided.”

Lastly, Roberts emphasizes three Smithian observations that remain highly relevant today. First, self-sufficiency leads to poverty. Societies that spend all their time gathering, growing, and cooking food remain trapped in subsistence living. Specialization and trade are essential for generating economic prosperity. Second, humans should concentrate more on their behavior rather than on how they wish others would act. People don’t want to be chess pieces moved around against their will. Lastly, on a lighter note, Smith points out that individuals often care more about a product’s elegance than its functionality. Even in the eighteenth century, he criticized gadget enthusiasts.

Russ Roberts offers a readable summary of Smith’s dense, though perceptive, classic. He dispels myths and provides pithy insights elucidating the key features of the Scottish thinker’s moral philosophy. I recommend that people read or re-read this book to better cope with and thrive in today’s challenging times.

Discover more from Researching the American Revolution

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.