Book Review

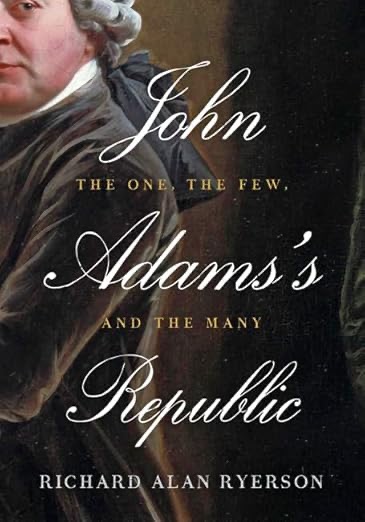

Ryerson, Richard Alan. John Adams’s Republic: The One, the Few, and the Many. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016.

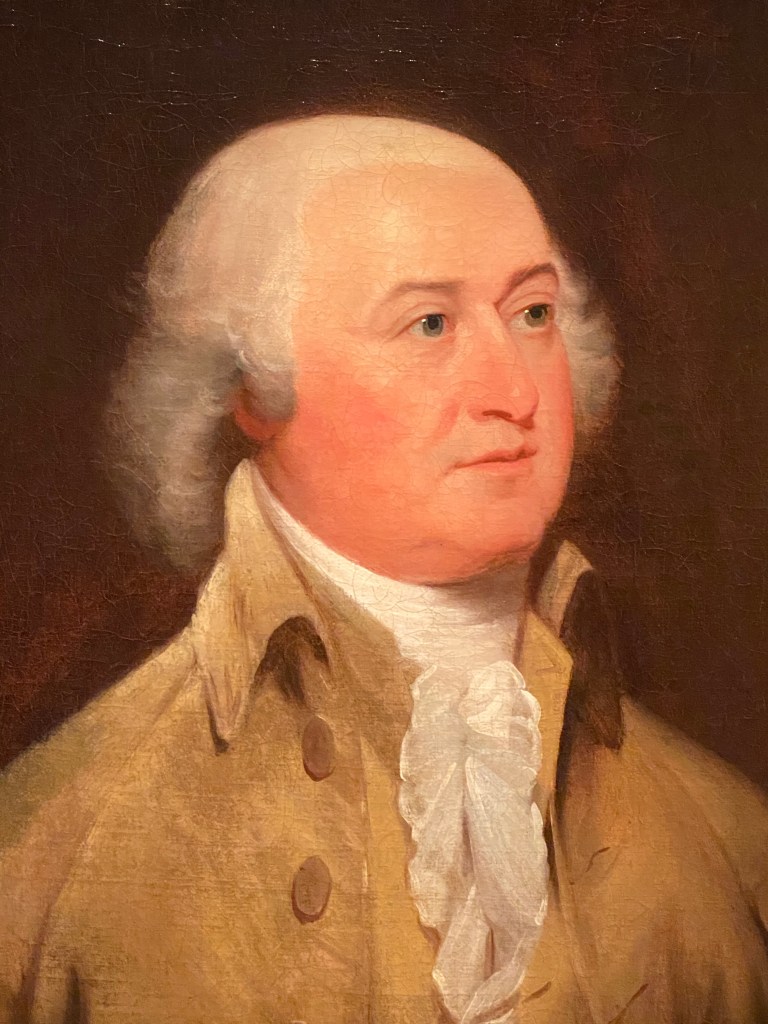

Contemporary critics and later historians have mockingly dubbed John Adams as “Mr. Rotundity,” emphasizing his short stature, ample girth, and supposed advocacy for monarchical elements within the new American political framework. Richard Alan Ryerson contests this viewpoint in a compelling and thorough reassessment of Adams’ political philosophy. Ryerson, a former editor-in-chief of The Adams Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society, contends that Adams believed successful republican governments necessitated balancing the powers of the one (the executive), the few (the aristocracy), and the many (the politically engaged populace). The author concludes that Adams’ most insightful contribution is controlling a natural aristocracy of society’s most affluent or accomplished individuals to dominate politically, which is the most vital aspect of constructing a new governmental system.

As an emerging lawyer, John Adams was a prolific researcher, writer, and political commentator before the American Revolution. Opposing the Tea Act of 1773 and the subsequent Coercive Acts, Adams penned thirteen articles for the Boston Gazette under the thin guise of the pseudonym Novanglus. Adams argued that the colonies were not subject to Parliament’s authority. While out-of-town newspapers did not widely reprint the Novanglus letters, Adams gained a reputation for independence advocacy and political theory acumen among the colonies’ senior revolutionaries. As a result, Adams’ colleagues sent him to attend the First and Second Continental Congresses in Philadelphia.

During the Second Continental Congress, the Massachusetts delegate argued indomitably that the colonies should replace their royal charters and governors with republican governments established by state constitutions. Borrowing from James Harrington, a seventeenth-century English proponent of republicanism, Adams defined a republic as “a government of laws, and not of men.” Harrington based his views on the political experiences of ancient Greece, Rome, and Renaissance Italy, which appealed to Adams’ historical interests and opinions on sound, constitutionally-based government. Ryerson avers that Harrington’s thinking “lay at the center of John Adams’s political writings” (p. 147).

Congressional delegates regarded Adams as Congress’s authority on constitutionalism based on his deep historical knowledge of republics and their operations. As Congress’ most historically conscious political thinker, numerous delegates sought Adams’ advice to share with their colonial constitution-making bodies. So taken with Adams’s constitutional recommendations, Virginian Richard Henry Lee had Adams’ recommended basic plan of government, Thoughts on Government, published anonymously by newspaper publisher John Dunlap in Philadelphia. Newspapers throughout the colonies widely reprinted Adams’ plan of government. Over half of the twelve new constitutions[i] exhibit Adams’ governmental form components, such as bicameral legislatures with popularly elected houses that, in turn, would elect a council and the election of a governor and other executive officers by a joint ballot of the house and council (page 173). Other key recommendations included an absolute veto power for the governor and an independent judiciary. Adams would advocate for this basic form of government for the next fifty years.

In 1780, John Adams drafted Massachusetts’ first constitution. Although the adopted version did not include all the provisions advocated by Adams, the Bay State’s new framework of government reflects many of his views: a bicameral legislature, a stronger executive, and an independent judiciary. Ryerson concludes, “Adams established the strongest and most durable foundation of any government in Revolutionary America” (p. 231). As a testament to Adams’ work, the Massachusetts Constitution is the oldest written constitution still in effect today.

While serving as a diplomat in Europe in the late 1780s, Adams chafed at French intellectuals’ challenges to the American state constitutions. He perceived European ignorance regarding America and vociferously opposed the notion that thriving republics required weak executives and unicameral legislatures. As a result, he researched and wrote about the history of republics from ancient Greek and Roman eras to contemporary times. Adams published his work in three volumes under In Defense of the New Constitutions of Government of the United States of America. In the opening volume, Adams argues that republican governments should combine features of classical republics and English constitutionalism to form a balanced three-branch government. The American reception was mixed, especially among the emerging Jeffersonians, who perceived Adams as attempting to import Europe’s monarchies and aristocracies into America.

After serving as the U.S. ambassador to Europe for three years, Adams returned to Boston in 1788. Although he did not personally participate in drafting the United States Constitution, the convention incorporated many of Adams’ principles into their final product. His public stature as a leading revolutionary was sufficient to be elected as the country’s first vice president. Even in a low-key position, controversy over Adams’ republican views intensified during the first years of George Washington’s administration. Adams’s outspoken advocacy of “His Highness,” “His most benign Highness,” or “His Majesty, the President.”[ii] for the President’s title tarnished him with many of his peers, labeling the Vice President a closet monarchist. Additionally, Adams anonymously published a series of essays titled “Discourses with Davila,” which furthered contemporaries’ perceptions that, while in Europe, he acquired monarchical and aristocratic tendencies. By 1791, the first vice president was publicly branded as a “closet” campaigner for a hereditary monarchy and family-based aristocracy.

While not disputing his advocacy of a monarchical-sounding presidential title was a mistake, Ryerson presents solid evidence that Adams did not return from Europe with a predilection for monarchy and aristocracy. Quite the opposite, the author asserts that Adams returned with an intensified fear of the aristocracy’s control over the executive branch and the populace. Adams believed all societies develop a natural aristocracy since influential individuals would always exist through inheritance, successful business endeavors, or differential knowledge. He witnessed an unbridled political aristocracy in both European republics and continental monarchies. Wary of the power of the “few,” Adams perceived a non-noble aristocracy emerging with burgeoning political influence in the United States. Even in retirement and well into his late seventies, the Braintree, MA resident penned letters advocating eternal vigilance against aristocratic powers.

Ryerson’s insights into Adams’ novel views on “the few” remain highly relevant for readers today. Adams’ central conclusion is that human nature is inherently flawed and that a balanced republican government is necessary to ensure societal happiness, including for its most vulnerable members. From his first political essay in 1763, “All Men Would be Tyrants,” to his last reflections sent to John Taylor of Caroline on balancing governmental power, Adams doggedly sought political solutions to manage the inevitable emergence of aristocracies. He believed that aristocracies naturally occur, cannot be destroyed, and must be harnessed for the public good. He did not see this challenge as easy as the aristocracy’s most aggressive members may place their “desire to acquire wealth and political power above any sense of obligation to serve the public good” (p. 393). Adams viewed extensive public education and an informed electorate as a means of countering the threats of an unbridled aristocracy and ensuring honorable public service.

As the second president predicted, over the past two hundred and fifty years, Americans have grappled with controlling various aristocratic elements, whether characterized as long-term career politicians, wealthy planters, industrialists, technologists, or other elite groups with disproportionate political power. Ryerson’s book is especially pertinent today as we evolve our democracy to maintain a government of laws, not men, and balance tripartite government to address emerging threats. John Adams would recognize today’s aristocratic issues.

[i] Rhode Island and Connecticut retained their corporate charters, only modifying them to remove references to the King and Parliament. Additionally, the self-proclaimed Republic of Vermont fashioned a constitution based upon the 1776 Pennsylvania government.

[ii] Congressman James Madison reported to Thomas Jefferson that John Adams advocated for “His Highness the President of the United States and protector of their liberties” as the presidential title (p. 319).

Discover more from Researching the American Revolution

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Can it be concluded the actions and achievements of Adams, as President, support the philosophical and political views Ryerson subscribed to Adams? I will do some research, but interested in any follow-up that would confirm or detract from Ryerson’s assertions.

Thank you

>

LikeLike

Ryerson compares Adams’ presidential actions with his philosophy and political views. For example, Ryerson points out that Adams strongly advocated for an absolute presidential veto (Congress may not override) but never used his veto powers even once as president. In many other areas, Adams consistently implemented his philosophy and political views.

LikeLike