The Revolutionary War in Salem, Massachusetts

Book Review

Morris, Richard J. Salem in the American Revolution. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2025.

Historians and readers often overemphasize the rebellious activities in Boston, neglecting the seminal events occurring in nearby seaports. Richard J. Morris, a historian of colonial and revolutionary America, addresses this oversight with the first full-length book devoted to the revolutionary era in Salem, Massachusetts. Although a Bostonian by birth and upbringing, Morris developed a lifelong fascination with the history of Salem while earning his PhD from New York University. The now-retired academic has authored several scholarly articles on Salem, and this, his first full-length book, represents the culmination of a lifelong research interest in the subject.

Morris anchors his narrative with the story of four gentry families: the Browns, Turners, Lindalls (later Fryes through marriage), and Lyndes. Before the struggle over British trade policies, these families exercised political control over the coastal community (p. 114). Professor Emeritus Morris introduces Robert E. Brown’s concept of “deference democracy” to explain why these four families dominated Salem’s late colonial politics (p. 24). In a 1955 book, Brown argues that male heads of household voted primarily to elect their social and wealthier superiors, which, in Morris’s view, contributed to the control that the four families had over Salem’s late colonial politics.[i]

Alternatively, later historians have argued that by the time of the American Revolution, elections had become more participatory (J. R. Pole), influenced by increases in republican ideology (Gordon Wood), market individualism (Joyce Appleby), and religious revivals (Rhys Isaac). While the author demonstrates that members of the four families held numerous elective and appointive positions, readers would benefit from understanding the controversy surrounding “deference democracy” and why Salem-specific voting or other evidence more fully supports this concept than other locales. On the other hand, the former Lycoming College professor provides an extensive analysis of income and wealth, leading to differing loyalties, as suggested by Appleby. He concludes that Salem was more prosperous than Boston, a lesser-known comparison.

In another area, the author disputes the notion that other historians hold that Salem was more conservative than Boston and initially offered lukewarm support for the Rebellion. He cites the town’s deliberate and peaceful approach as a positive rather than a negative. He notes that the town’s name connotes “a city of peace,” but that did not mean the town was willing to bow to British misrule (p. 93).

While Morris chronicles the well-trodden story of parliamentary taxes and coercive laws leading up to the outbreak of hostilities, he adds interesting aspects unique to Salem, the center of America’s cod fishing industry. First, he avers that the port city’s population was proud of its non-violent Stamp Act protests while just as rigorous in enforcing the resulting non-importation agreements. Later, the Townsend Acts spurred violence, including the burning of a customs boat and the tar and feathering of a customs house employee (p. 58). Second, he describes the little-known extension of the Seaman’s tax from sailors who landed in England to the colonial fishermen who stayed in American waters. The Seaman’s tax-supported the Greenwich Hospital, which assisted sick or injured commercial sailors who arrived in England but not fishermen who stayed in American waters. After the Townsend Acts, a new customs board extended the Seaman’s tax to local fishermen, which was bitterly opposed by Salem’s fishing industry. Lastly, through a quantitative analysis, he dispels the perception that Salem was more loyalist-leaning and less supportive of the rebellion.

Further divisions in politics and loyalty arose within the Salem community after its citizens learned about Parliament’s 1774 Coercive Acts and the closing of Boston Harbor. The Earl of Dartmouth ordered General and the new Royal Governor Thomas Gage to move the Massachusetts Colonial capital to Salem. Residents sent two letters to Gage upon his relocation to Salem, illustrating this stark divide. The first letter was signed by forty-eight of the town’s elite, twenty-nine of whom benefited from royal appointments. Only three Salem-born individuals in this group were not connected to the four families. The second group consisted of 125 emerging merchants, mechanics, mariners, and artisans, indicating that the supporters of the rebellion were more numerous. Only one person in this group held an appointive office. A key strength of Morris’ argument lies in a detailed examination of the socioeconomic data of Loyalist and rebel supporters, particularly in areas such as wealth, income, and inheritance. Based on his data analysis, Morris concludes that occupation, wealth, and family connections, rather than ideology or cultural ties to England, determined individuals’ membership in these two groups.

Upon Gage’s arrival in Salem, he responded to the first letter with “favorable sentiments” and the second in cooler terms, as reported in the Essex Gazette. Another of the book’s strengths is its extensive use of the local newspaper as a primary source. The newspapers provide a public view of the residents who lean towards the Rebels and those who lean towards the Loyalists, as well as Thomas Gage’s official reactions. It would have been intriguing if the author had found any personal, non-public responses to the two letters by Gage or other British officials to offer a more well-rounded view of their stay in Salem.

When war erupted, the character of Salem’s maritime industry changed dramatically. The British government shut down the town’s fishing industry, causing significant economic distress. To utilize the town’s maritime expertise, ship owners converted the pre-war commercial fleet into privateers to raid and capture British merchant ships. At least 158 privateers sailed from Salem Harbor. The economic impact of prize money awarded to ship owners and crews sustained the town’s economy during the eight-year conflict. As the privateering activity was the most significant contribution by Salem to the Patriot cause, the author’s narrative could have been enhanced by consulting privateering historians and expanding the section to place Salem’s commerce raiding activities in a larger context. For example, the author of the latest book on American privateering notes that Salem merchant Elias Hasket Derby was one of the most active raiders, owning or partially owning thirty-nine ships, a quarter of Salem’s fleet.[ii] Another privateering historian estimates that Salem ships accounted for almost ten percent of Massachusetts and Continental Congress’s authorized privateers, capturing over 450 British vessels as prizes.[iii] As a result, while no land battles were fought in the area, Salem was a major contributor to the war effort.

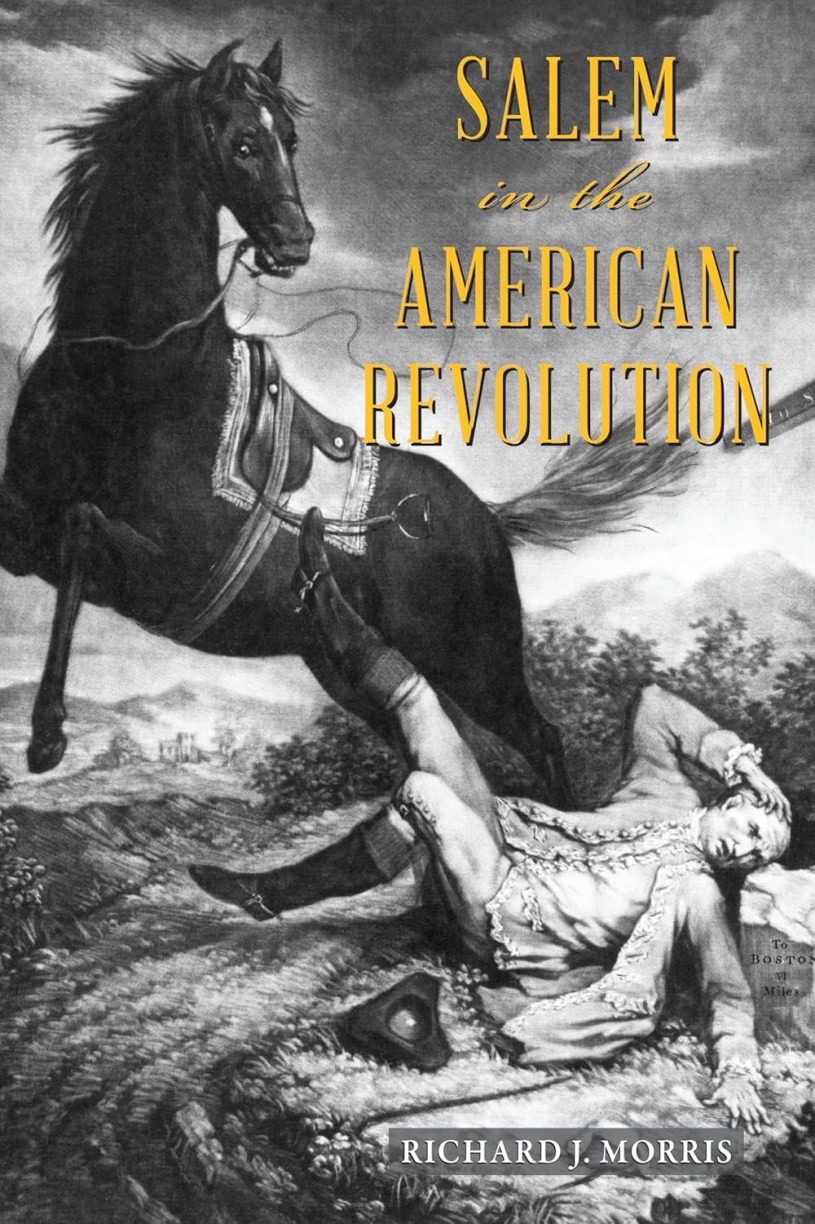

The book’s illustrations and cover feature some quirky aspects. The author recreates pamphlet covers, manuscripts, and town records using modern script text without rationale. Copies of period documents would attract greater interest, as Morris does with the Essex Gazette newspaper headlines. The book’s dark and foreboding cover will likely remain a mystery to most readers. The 1774 mezzotint by British satirist John Dixon depicts a rider thrown from a horse beneath stormy skies at the six-mile mark on the route from Boston to Salem. The turbulent skies signify the impending rebellion, while the bucking horse represents the American colonists, and the rider symbolizes either Governor Gage or British Prime Minister Lord North.[iv] The book’s title obscures a sign pointing to Salem in the original piece. Connecting the cover with the manuscript may enhance reader comprehension.

In the case of Salem during the American Revolution, I advise potential readers not to judge the book by its cover. Salem’s divided loyalties, evolving sentiments in favor of independence, and the war-transformed maritime industry are captivating and relatively overlooked aspects of Revolutionary America, particularly for a vibrant coastal city like Salem. Furthermore, everyone will gain from the extensive and engaging economic and social statistical insights that the author has gathered through a lifetime of research on colonial and revolutionary Salem.

[i] Brown, Robert E. Middle-Class Democracy and the Revolution in Massachusetts, 1691–1780. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1955.

[ii] Eric Jay Dolin, Rebels at Sea: Privateering in the American Revolution. (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2022), 50.

[iii] Donald G. Shomette, Privateers of the Revolution: War on the New Jersey Coast, 1775-1783 (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd, 2016), 32.

[iv] For more interpretive information on the book cover see J. L. Bell’s Boston1775 article, https://boston1775.blogspot.com/2015/.

Discover more from Researching the American Revolution

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.